-

Bruce Northam

Bruce Northam

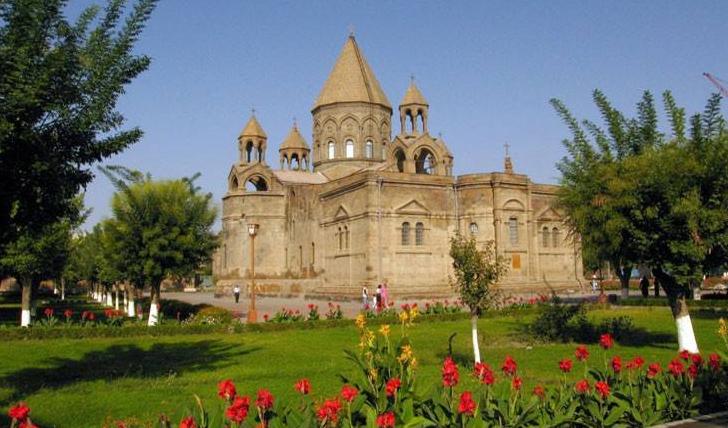

Holy Echmiadzin, Armenia / Photo: Hovhannes Margaryan

Armenia: Europe’s Final Frontier

Views - 2089

Although surrounded by Arab countries, this cradle of Christianity remains Europe’s last undiscovered corner. Not only do most people have no idea where Armenia is or what it stands for but they’ve also yet to discover this tiny country’s massive will to prosper—at home and around the world.

For a country I’d previously had to plead ignorance, this is a story about what I found and loved in Armenia, which was pretty much everything. The first thing you’re bound to realize when arriving in this country that flies low under the radar is that even most veteran travelers can’t find it on a map.

Let’s fix that. Bordered by Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, Turkey, and autonomous Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia is part of the Caucasian Plateau. It gets along fine with Iran and Georgia; Turkey and Azerbaijan, not so much.

It is actually the only country in the world that has closed borders with two neighbors—Azerbaijan and Turkey. Despite having two gnarly neighbors, it remains one of the safest countries in the world. We’re talking in a safety league with Japan or Switzerland. The great news continues.

Armenian woman in Armenian national dress—a taraz / Photo: Bruce Northam

Smart. Really Smart

Soonafter getting your bearings, it hits you that Armenians are smart. Really smart. Armenia’s number one export seems to be brains. Its long-standing academic tradition is traced to its first school, established in 406AD, which taught the Armenian language and the art of translation. The country enjoys a 99-percent literacy rate.

Armenians regularly catapult themselves into the world’s leading schools via scholarships, foundations, and wealthy Armenian expat contributions.

Their smarty-pants reputation is likely linked to their ancient and versatile alphabet, whose 39 characters include two different sounds for e and r. Armenian is an Indo-European language and related to English.

Unlike the U.S., where men dominate the tech sector, 50-percent of Armenia’s techies are female. Chess—the brainiest of games—is a national pastime that’s taught as part of the school curriculum as a competitive sport, typically by the same teachers that instruct all things military.

As a result, Armenia has spawned many chess champs, including Grandmaster, which is the highest title a chess player can attain. Once achieved, the title is held for life.

Armenian Roots in the USA

It’s also likely that you already know somebody with Armenian roots. Eighty percent of Armenian surnames end in either ian or yan. Ian or yan (translated from Armenian) is an Indo-European postfix/suffix that shows belonging.

Vorotnavank monastic complex / Photo: Bruce Northam

It’s identical to the -ian as in Washingtonian, Smithsonian, Bulgarian, and Kardashian.

It doesn’t take long to realize that Armenia is ancient like Europe, but way cooler. The real mindblowers here have religious origins, but you don’t have to be religious to enjoy them.

The Connecticut-sized country has thousands of ancient monasteries and churches, several of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. (Take that, “classic” Europe: have fun waiting in endless lines for tourist traps.)

And, Armenia’s religious sites are always open. The priests inhabiting these mountain-encircled landmarks have wives and families and can relate to your way of life—they might even invite you to enjoy some wine. And there’s no shortage of raptors soaring above these monastic complexes.

Enter Marmashen Monastery, built in 988 using groundbreaking and later duplicated solid construction in a rural midst-of-nowhere setting that’s also a seismic zone. Earthquakes are common in Armenia. Yes, they know how to shake things up.

Armenia is not all about churches. High culture is low priced here. Armenia has a long-established tradition of music. One can go to a world-class opera performance for only $6. Armenian jazz, a distinct art-form sprung from Armenian folk music, was famous during the Soviet era and is making a comeback on the global stage.

Actually, pretty much everything here is incredibly cheap. Cabs, cafes, wine, beer, divine restaurants, and groceries (three pounds of organic tomatoes for 30 cents) are enjoyed for 1960’s U.S. prices.

A Land of Toasts

Gurdjieff Ensemble in Villa Kars courtyard / Photo: Bruce Northam

You’ll also quickly learn that Armenia is a land of toasts, where endless meals are punctuated by raised-glass celebrations and conversation.

Sinfully wonderful food, music, scenery, and intellectual banter is the norm. Small towns, like up-north Gyumri, are great places to begin this discovery.

Gyumri’s Villa Kars, the living dream of an Italian expat, is a restored survivor of the devastating 1988 earthquake. The basic-but-pleasing hotel surrounds a garden courtyard.

The all-organic menu in the homey dining area is an avalanche of perfectly cooked and seasoned vegetables (vegetarians smile wide in Armenia) that will even satisfy hardcore carnivores.

Cascade complex, Yerevan / Photo: Bruce Northam

The meat always arrives in Armenia, but not until you’ve been wowed by a few courses of veggies. The hotel occasionally hosts courtyard concerts. I was lucky to see the world-touring Gurdjieff Ensemble, an ethnographically authentic instrumental world-music group playing traditional Armenian instruments.

Many of Gyumri’s buildings are fashioned with large, dark volcanic stone blocks. While some of its stone structures survived the devastating 1988 earthquake or were rebuilt, most of the flimsy Soviet-era construction did not survive here.

The Gyumri Ceramic School keeps the art of glazed-clay alive, where the owner (translated) “Hoped not to abuse my patience.”

St Saviour's Church, Gyumri / Photo: Bruce Northam

Alexandrapol Brewery also captures this sleepy town’s architectural style, which mishmashes Persian, Russian Empire, modernist, Art Deco, and Art Nouveau.

Gorki Park is a green break from the trance of dark-block architecture. Work on Gyumri’s St Saviour’s Church started in the 1850s, and continues today (note facelift crane) courtesy of the 1988 earthquake.

The Berlin Art Hotel’s 15 rooms each feature a room from a different local artist, and its backyard is a nice place to take in the travelers’ scene.

Conservation and Ecology

Another facet of Armenia’s emerging tourism sector is preserving nature via conservation and ecology. Armenia’s diverse elevations and microclimates host approximately 360 bird species (all of Europe has 450).

The northeast’s mountainous Caucus-crossroads is bird terrain where high-elevation grassy meadows eventually give way to seldom-visited Lake Arpi National Park, which sits at 6000 feet within sight of the country of Georgia.

En route, we passed isolated farm communities and caucasian brown cows, owl-resembling kestrals, white pelicans, wolves, and lone shepherds. Wildness.

Family Style Dining

You’ll spend a lot of time dining family style here.

A long-table dinner at Gyumri’s Triangle “forgery” restaurant with its sixth generation blacksmiths is when I learn about Armenia’s incredibly low crime rate, more on it being a vegetarian’s heaven (but taking nothing away from the aubergine: eggplant with beef), and how the constant meal-toasting culture helps people pace their wine intake as the avalanche of plates of unending food options arrive, a shared culinary carnival where all diners are in reach of varieties of veggies, cheeses, and grilled meats.

A feast at Gyumri’s Triangle restaurant / Photo: Bruce Northam

And, oh yeah, it is the apricot capital of the world. Mountainous Armenia’s fertile valleys are perfect for growing apricots. They even make brandy out of them. Apricot’s scientific name is Prunus Armeniaca (Armenian plums). Unlike locals, visitors often bite right into them.

Locals, however, always break them open to check for worms first, because Armenian apricots along with all produce are always organic and non-GMO (without a price markup). Redefining women’s sometimes repressed role is also on the menu here, where an emerging social justice platform is being built around creating legal language to define previously undefinable things like domestic violence and orphans at risk. This is a country on the move.

Armenia makes great wine, which they’ve been producing for a long time. The Agarak Archeological Complex, dating to 4th Century BC, has cultic graves and ancient wine presses (that now ferment frogs).

Ancient wine press at Agarak Archeological Complex / Photo: Bruce Northam

But the living proof for sommeliers waits at Voskevaz Winery, whose all-things-wine campus includes an artisanal wine collection hall.

I sampled a few ancient wine varieties and their “Golden Berry” chardonnay while dining with current U.S. Ambassador Richard Mills, who revealed that the U.S. Embassy, built 2005, was the world’s largest until the 2008 completion of Iraq’s American embassy.

Rick also confessed that he was once the doorman at a Detroit retirement community. Wine is another sampling of how this underrated star of a nation is coming out of hiding.

Author with U.S. Ambassador to Armenia Richard Mills at Voskevaz Winery

Yerevan

Yerevan, a city captured by the allure of Turkey’s soaring ice-capped Mount Ararat, is the most likely place you will encounter Armenia’s intellect.

But Yerevan is about fun too, whether that means dancing in a smoking-hot Latin American-style dance club, smoking a hookah with locals and European tourists, or sipping a craft beer in a trendy bar.

Once Sovietized but now recovered, one of the world’s longest continuously inhabited cities is laid out in a circular sun-halo grid.

One centerpiece is the Cascade, a multi-level outdoor and indoor public art gallery.

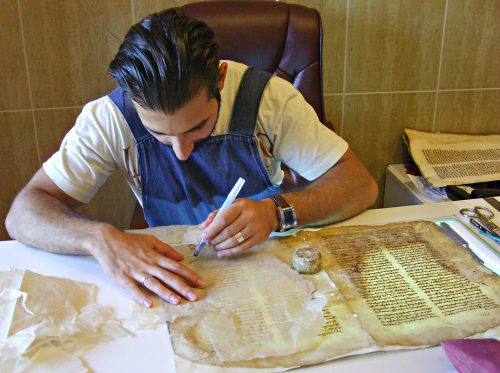

Armenia also experienced a genocide. But to really drill down into what makes these people tick you’ve got to visit the Manuscript Museum’s worldwide collection of documents that starts from 887 and includes partial and complete manuscripts on parchment, paper, leaves, bark, animal skins, some within elaborately decorated 6th century ivory bindings.

Restoration of ancient manuscripts and the evidence of the Armenian genocid, Matenadaran Museum, Yerevan / Photo: Bruce Northam

Their Restoration Department stays busy maintaining more than 23,000 manuscripts including 10,000 from outside Armenia.

80,000 manuscript were destroyed during the Armenian genocide perpetrated by Turks before WWI.

This genocide also killed 1.5 million people, which still doesn’t get the recognition it deserves.

Although this plight has received attention both academically and diplomatically, Turkey refuses to recognize it as a genocide.

Yerevan’s incredibly stirring Genocide Museum will never stop fighting for the justice they deserve for enduring this horrible moment in history.

With tourism emerging as one of its many promises, this rising underdog country is poised to make its mark—once again.